Aldo Leopold introduced the concept of a “land ethic.” He fundamentally challenged us to rethink our relationship with the land. Land, according to Leopold, is about more than just economic exploitation.

He taught us that we need to listen to nature and what it’s telling us. His Sand County Almanac became one of the most important and influential works of the environmental movement.

Leopold’s land ethic grew out of his lifetime of experiences and values. As an author, philosopher, naturalist, scientist, ecologist, forester, conservationist, and environmentalist, Leopold was a leader of the Conservation Movement in America.

Aldo Leopold helped give birth to the Modern Environmental Movement.

He is one of More Than Just Parks Environmental Heroes.

The Frontier In American History | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

When Aldo Leopold was growing up Frederick Jackson Turner formulated a theory to explain the relationship between Americans and the land. He called his idea “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner wrote, “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.”

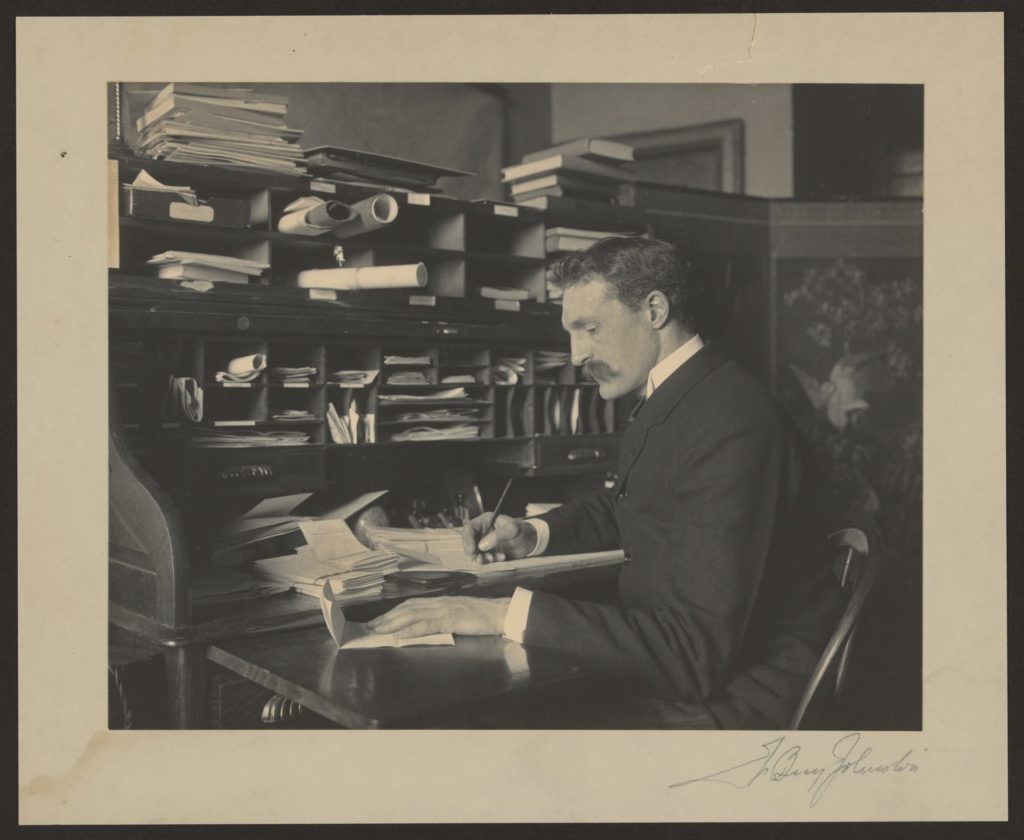

Carl Leopold

Aldo Leopold acquired his love of the land from his father, Carl. He taught all of his children to appreciate the natural world. By the time he was thirteen years of age, Aldo, who was the oldest of the Leopold children, was accompanying his father on hunting trips.

“With his long face and bushy, brown, upturned mustache, he was sometimes mistaken for Kaiser Wilhelm, but in attitudes and interests he resembled no one so much as a man he much admired, Theodore Roosevelt.

Like the soon-to-be president, Carl Leopold was a positive, firm man, though perhaps not so bullying; he had a adventurer’s passion for the outdoors, but also a naturalist’s understanding of it; and in his view of society, he was both conservative and progressive at the same time.

Unlike Roosevelt, he was not a student of history, nor did he make history in such a prominent way. But he could read history in what was happening to the natural world he loved.”

-Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work

The Yale Forest School | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

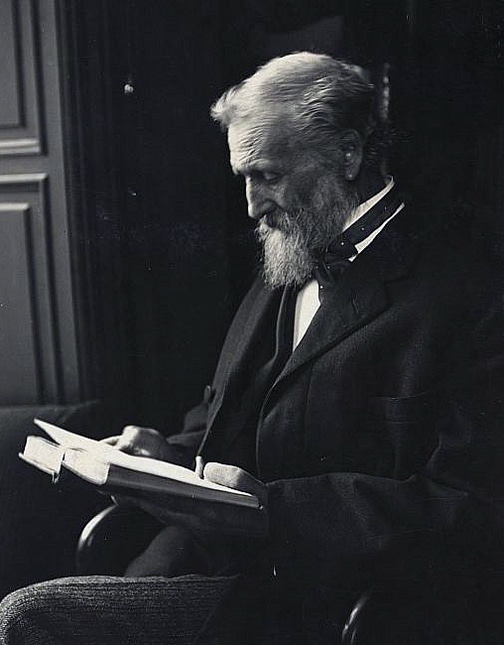

Gifford Pinchot was the first director of the U.S. Forest Service. Prior to the creation of the Forestry Service in 1905, Pinchot helped to create America’s first school of forestry at Yale University in 1900.

Pinchot was the first American to receive professional forestry training in Europe. The School was founded with a gift from the Pinchot family to ensure a continuing supply of professionals to carry out the work of forest managment.

Five years after the school’s creation, Aldo Leopold enrolled in the Sheffield Scientific School, which offered Yale undergraduates a preparatory training program before moving on to his studies at the forestry school.

Leopold completed his work as a graduate student in 1908-09. From there, his career began as a forester. Leopold would begin the next phase of his education.

RELATED: Gifford Pinchot: A 2021 Lesson From America’s First Forester

“Leopold was a naturalist and a hunter who became a forester. Yet, his own attitudes, shaped by a strong father, a devoted mother, a rich experience of natural surroundings, and a strong inner drive, were too independent to be dominated by anyone, or by any idea. . .

His greatest asset was not his intelligence, or perceptivity, or spirit, or conviction, although he possessed all of these in abundance. His greatest asset was his independence, and his awareness of the interdependence that allowed it.”

-Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work

The Education Of A Forester | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

Apache National Forest

Leopold’s first assignment was the Apache National Forest. He would be out for several months at a time to inventory the land and estimate the available timber reserves.

Leopold had been taught the utilitarian approach to conservation whereby people have a right to use natural resources, but also an obligation to use them wisely and efficiently.

His boss, Gifford Pinchot, referred to this approach at “the greatest good for the greatest number over the long run.”

Carson National Forest

Leopold’s second assignment took him to the Carson National Forest. Here he saw firsthand the impact of soil erosion on the land. Sheep, whom John Muir once referred to as “hoofed locusts,” had been allowed to graze.

This grazing decimated the grasslands. Leopold began to see the limitations of the utilitarian approach.

He then became supervisor of the Carson National Forest. While on an extended trip in 1912, he found himself sleeping in a soaked bedroll after a hailstorm hit. Leopold returned with his face, hands, arms, and legs swollen.

Bright’s Disease

He had contracted Bright’s Disease. Leopold’s kidneys had failed, toxins had built up in his system and he took a six week sick leave unaware of the fact that he would not return to the Forest Service for almost two years. He was, however, lucky to have survived.

From Forestry To The Protection Of Wildlife | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

After sixteen months, Aldo Leopold finally returned to the Forest Service. When he did, he was thinking about more than just the management of timber and other forest resources.

As a child, he had been drawn to wildlife through his hunting expeditions with his father. Increasingly, Leopold became concerned about the future of wildlife and whether, in fact, there would be any species left to hunt.

“North America, in its natural state, possessed the richest fauna in the world. Its stock of game has been reduced 98%. Eleven species have been already exterminated, and twenty-five more are now candidates for oblivion.

Nature was a million years, or more, in developing a species . . . Man, with all his wisdom, has not evolved so much as a ground squirrel, a sparrow, or a clam.”

-Aldo Leopold, U.S. Forest Service Game Handbook

Wilderness Preservation

Aldo Leopold left the Forest Service in 1918 to take a job with the Albuquerque Chamber of Commerce. He rejoined the Forest Service a year later as an Assistant District Forester in Charge of Operations.

He was now on the frontline of changes threatening the long-term viability of the American Southwest. This job, like all of the previous ones, formed a part of his education.

Increasingly, Leopold came to embrace wilderness preservation as a crucial component of any viable long-term land management plan.

“When the National Forests were created the first argument of those opposing a national forest policy was that the forests would remain a wilderness . . . At this time, Pinchot enunciated the doctrine of ‘highest use,’ and its criterion, ‘the greatest good for the greatest number,’ which is the guiding principle by which democracies handle their natural resources.

Pinchot’s promise of development has been made good. The process must, of course, continue indefinitely. But it has already gone far enough to raise the question of whether the policy of development (construed in the narrow sense of industrial development) should continue to govern in absolutely every instance, or whether the principle of highest use does not demand that representative portions of some forests be preserved as wilderness.”

-Aldo Leopold excerpted from Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work

Leopold Outgrows The Forest Service | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

Aldo Leopold’s final job with the U.S. Forest Service was as assistant director at the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin.

He had established himself as a pioneer in national forest policy and was becoming one of the leading voices in the conservation movement.

For Leopold, however, the Forest Service was no longer the appropriate venue for his growing list of interests and causes.

He moved on to work as a wildlife specialist for the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute before becoming, like Gifford Pinchot before him, a consulting forester.

Professor Leopold

Aldo Leopold’s final career move took him into the classroom. He became a professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin.

From this position, he went on to become a founding member of the Wilderness Society and was active in numerous professional organizations.

The Land Ethic

More importantly, Leopold began to train the next generation of conservationists while continuing his research into what would became known as the “land ethic.”

Leopold was a popular professor who had hundreds of undergraduate students interested in taking his courses. He also worked closely with a number of graduate students who made contributions of their own to the growing cause of conservation and environmentalism.

“Over the next three and a half years, in many ways, the most complex years of his life, Leopold would strive to define accurately this new attitude toward land, and to apply it in his work. Over the course of his career, Leopold had grown into and out of a number of labels: Naturalist, Forester, Game Protector, Game Manager, Wildlife Manager.

The subtle distinctions in this progression of titles reflected changes in the purview of conservation generally and of Leopold personally. Without discarding either the techniques or perspectives he had gained in these previous roles, he was now ready to bring them to bear in a still broader calling, as a land manager, a land ecologist, and a teacher of both.”

– Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work

A Sand County Almanac | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

At the end of his career, Leopold assembled a collection of essays. His plan was to publish these essays with a unifying theme which embraced his land ethic. Leopold was in the process of completing his most important work when tragedy struck.

While fighting a fire near his vacation home, he suffered a massive heart attack and died.

A Critical Success

His son, Luna Leopold, who had become a conservationist, saw to it that his father’s final work was published. A Sand County Almanac was a huge critical success. At a time when others were predicting ecological catastrophe, Leopold’s book offered a ray of hope.

Published in 1949, the book encouraged a new generation of conservationists in the 1950s. In his book, Leopold defined conservation as “a state of harmony between men and land.”

This definition demonstrated his desire for a healthy relationship between the needs of man and the needs of the environment.

To Treat The Land With Respect

What Leopold did was urge humankind to treat the land with respect and not to base the value of everything simply on monetary gain. Leopold said that humans could no longer behave as the masters of everything by determining what should and what should not exist.

The message of his final work is that a healthy environment requires all of its parts working together.

The “Big Three” Of The Environmental Movement | George Perkins Marsh

Through their writings, three American authors have arguably had the greatest impact on the environmental movement. One was George Perkins Marsh.

Through his Man & Nature, published in 1864, Marsh was among the very first to include human impacts in our understanding of the natural world.

More than that, however, was his challenge to this notion, which dominated 19th century thinking; namely, that humankind’s efforts to shape its environment was always beneficial.

The fundamental message of Man and Nature is that nature does not heal itself from our destruction.

RELATED: George Perkins Marsh-The Father Of Climate Change

The “Big Three” Of The Environmental Movement | Rachel Carson

A second was Rachel Carson. Prior to Silent Spring, it was believed that humankind was the master of its own destiny. We could bend the physical universe to meet our needs.

Rachel Carson showed us that there were limits to how far the universe will bend in our favor. All life is interconnected. Actions have consequences. If we make life unfit for one species then we make it unfit for others as well, including ourselves.

RELATED: A Woman Started The Modern Environmental Movement (Can It Continue?)

The Legacy Of Aldo Leopold | Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic

Aldo Leopold was the final member of this important trio of authors whose works provide a foundation on which the modern environmental movement has built.

At a time when technological advances, such as chemical pesticides and nuclear weapons, placed our planet in increasing peril, Aldo Leopold brought a greater understanding of our relationship with the natural world.

Like George Perkins Marsh and Rachel Carson, he challenged the notion that all human impacts are beneficial.

Rethinking Our Relationship With The Land

Leopold challenges us to rethink our relationship with the land. Leopold’s early recognition of keeping and restoring biological diversity and ecological processes became central to his evolution of thought on the environment.

Leopold taught us that we need to listen to nature and what it is telling us. Our use of natural resources needs to become more intelligent. Leopold challenges all of us to seek alternatives which restore an essential balance and harmony within the natural world.

We owe it to ourselves and to generations yet to come to heed his wise words and follow his sterling example.

To Learn More:

- Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac, The Aldo Leopold Foundation.

- Meine, Curt. Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1988.

Leave a Reply