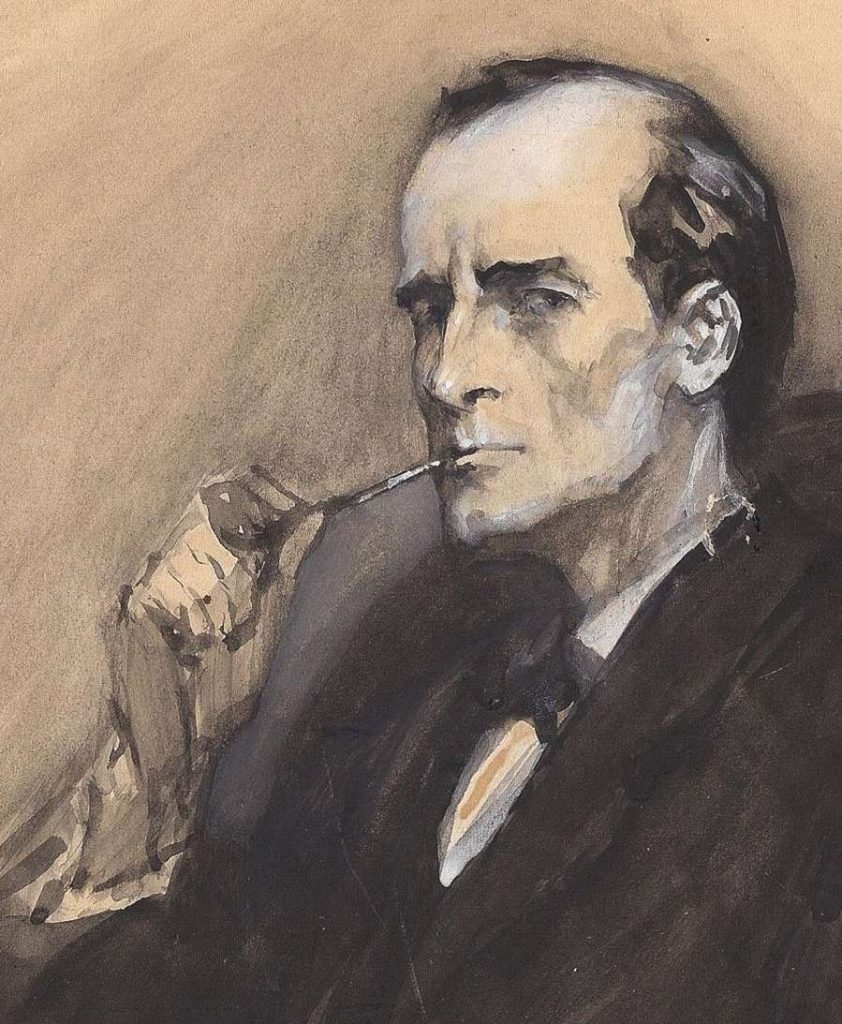

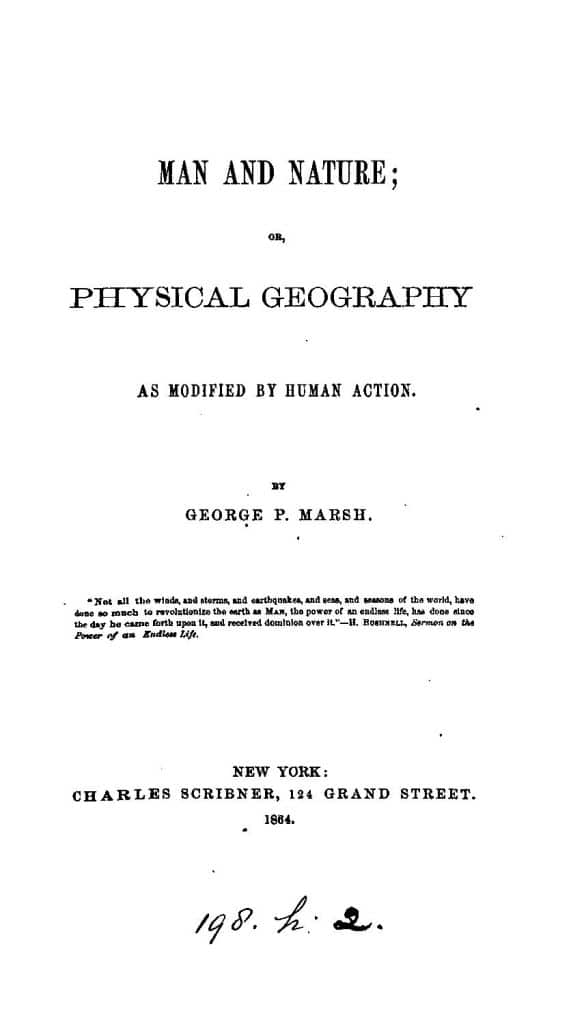

George Perkins Marsh was one of the first environmental leaders, some would argue the very first, to challenge the idea that human activity is always beneficial to the environment. In 1864, he published his groundbreaking work, Man and Nature.

Marsh charted the rise and fall of great civilizations such as the Roman Empire. He saw a connection between how these civilizations managed their natural resources and their long-term survival.

Marsh warned that humankind could destroy itself if it did not protect these precious resources. So, why does that matter today?

Sea levels are rising and oceans are becoming warmer. Longer, more intense droughts threaten crops, wildlife and freshwater supplies. From polar bears in the Arctic to marine turtles off the coast of Africa, our planet’s diversity of life is at risk from the changing climate.

Extraordinary heat waves are sending temperatures soaring into uncharted territory in Europe and the United States setting ghastly new benchmarks.

As we enter dangerous uncharted territory, More Just Parks takes a look back at the man who was the first to sound the warning. In doing so, he became one of the most consequential figures in the Environmental Movement. He is part of More Than Just Parks Environmental Heroes Series.

The First To Document The Effects Of Humans On Their Environment

“At a time when the United States was moving at breakneck speed to industrialize and develop the national economy by exploiting its wealth and natural resources to the fullest, Marsh’s was a lonely voice cautioning against the risks of careless growth.”

-David Lowenthal, George Perkins Marsh: Prophet of Conservation

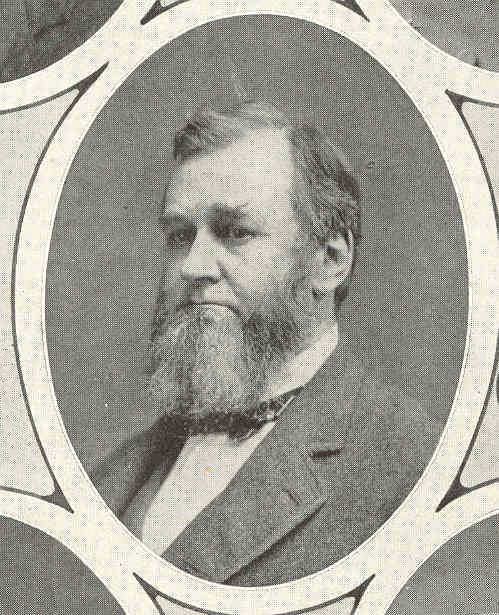

George Perkins Marsh

The “Big Three” Of The Environmental Movement

Rachel Carson

Through their writings, three American authors have arguably had the greatest impact on the environmental movement. One was Rachel Carson.

Prior to Silent Spring, it was believed that humankind was the master of its own destiny. We could bend the physical universe to meet our needs.

Rachel Carson showed us that there were limits to how far the universe will bend in our favor. All life is interconnected. Actions have consequences. If we make life unfit for one species then we make it unfit for others as well, including ourselves.

RELATED: A Woman Started The Modern Environmental Movement (Can It Continue?)

Aldo Leopold

A second author was Aldo Leopold. Leopold wrote A Sand County Almanac. His masterful work was considered the single most influential argument in support of wilderness and the establishment of a “land ethic” for Americans in the latter half of the twentieth century.

RELATED: Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic & How It Helped Give Birth To Environmentalism

Early Observations

George Perkins Marsh was the third member of the “Big Three.” And, he was the first to publish his findings.

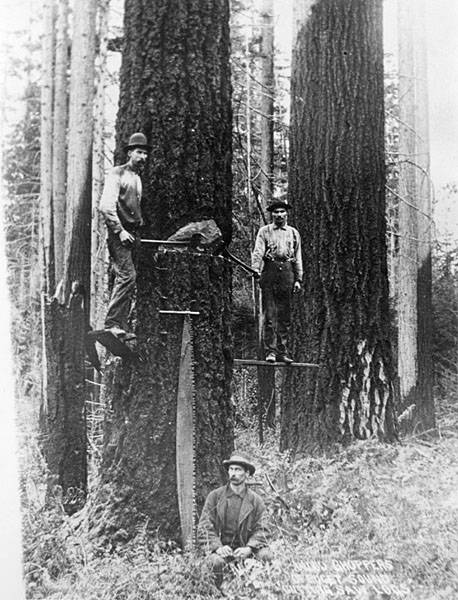

Marsh first became aware of the damage human activity could have on the environment as a child. He observed that, when farmers cleared their fields and cut down their trees, the barren hillsides could no longer absorb as much rainfall and snowfall.

Humans Believed Their Impacts Were Always Beneficial

This led to flooding which proved quite destructive. Today we take this as a given, but in Marsh’s time it was believed that human impacts on the environment were always beneficial.

Given his understanding of deforestation, Marsh began asking himself if there were other adverse consequences which came about as a result of manmade efforts to change the natural environment.

He spent the remainder of his life gathering evidence from across the globe to answer this question.

“He was the first to suggest that human beings were agents of change, or “disturbing agents.” The conventional idea held by geographers of the day, Arnold Guyot and Carl Ritter, was that the physical aspect of the earth was entirely the result of natural phenomena, mountains, rivers, oceans. No one had ever turned to the study of the earth as the home of humankind. Marsh was the first to describe the interdependence of environmental and social relationships.”

-George Perkins Marsh Institute, Clark University, About George Perkins Marsh

Nature Must Be Controlled

During the nineteenth century, people believed nature must be controlled. It was also believed that whatever humans did was always beneficial to their environment.

While Marsh subscribed to the notion that nature ought to be controlled, he also believed it required care and maintenance which set him apart from his contemporaries.

Follow The Evidence Wherever It May Lead

Another thing which set Marsh apart from his contemporaries was his unwillingness to accept certain propositions on faith alone.

Among the people of his time, it was believed that humankind was doing God’s work in its efforts to tame the wilderness. Marsh, however, believed it was important to weigh the results and act accordingly.

“He was not a great statesman; aloofness and aversion deterred him from seeking political prominence. He was not a great scientist; omnivorous curiosity and restless practicality precluded any single-minded dedication.

-David Lowenthal, George Perkins Marsh: Prophet of Conservation

It was in the borderlands linking science and the public weal that Marsh made his lasting contributions. He applied science to life, not with the disinterested precision of an engineer, but with the goals and means of a humanist. Marsh was a superb promoter of knowledge.”

A Man For All Seasons

George Perkins Marsh was a polymath or a person of wide-ranging knowledge. Marsh had not one, but many careers. He was a lawyer (though, by his own account, “an indifferent practitioner”), a newspaper editor, a sheep farmer, a mill owner, a lecturer, a politician and a diplomat.

He was also active in business, but failed miserably in every venture he undertook. From marble quarrying to railroad investments to woolen manufacturing, Marsh found ways to lose money.

Poor Investment Decisions

As a result of his poor investment decisions, he spent much of his life worrying about how he would meet his financial obligations.

Marsh also studied linguistics, knew 20 languages, wrote a definitive book on the origin of the English language, and was known as the foremost Scandinavian scholar in North America. George Perkins Marsh was truly a man for all seasons.

“All Nature is linked together by invisible bonds and every organic creature, however low, however feeble, however dependent, is necessary to the well-being of some other among the myriad forms of life.”

-George Perkins Marsh

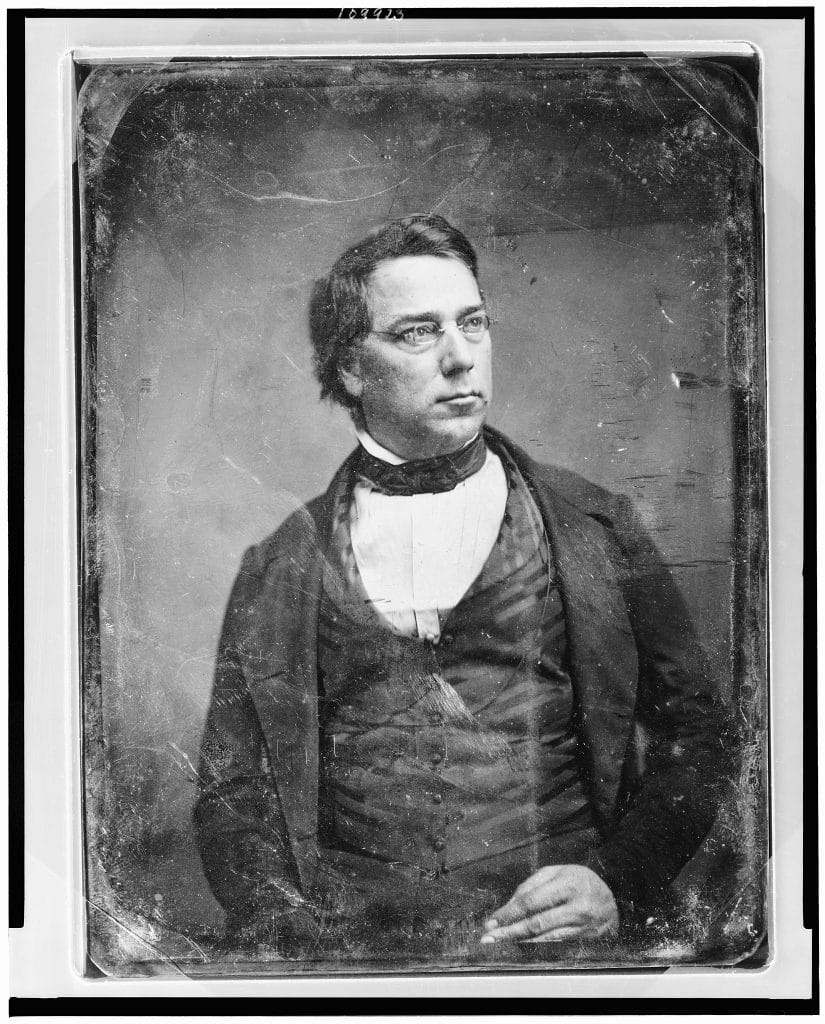

Congressman Marsh

Early on, George Perkins Marsh was recognized as a scholar and found himself increasingly involved in the public affairs of his native Vermont. In this regard, he followed in the footsteps of his father.

Charles Marsh had served as a member of Congress. He used his position to make sure his son received a strong education.

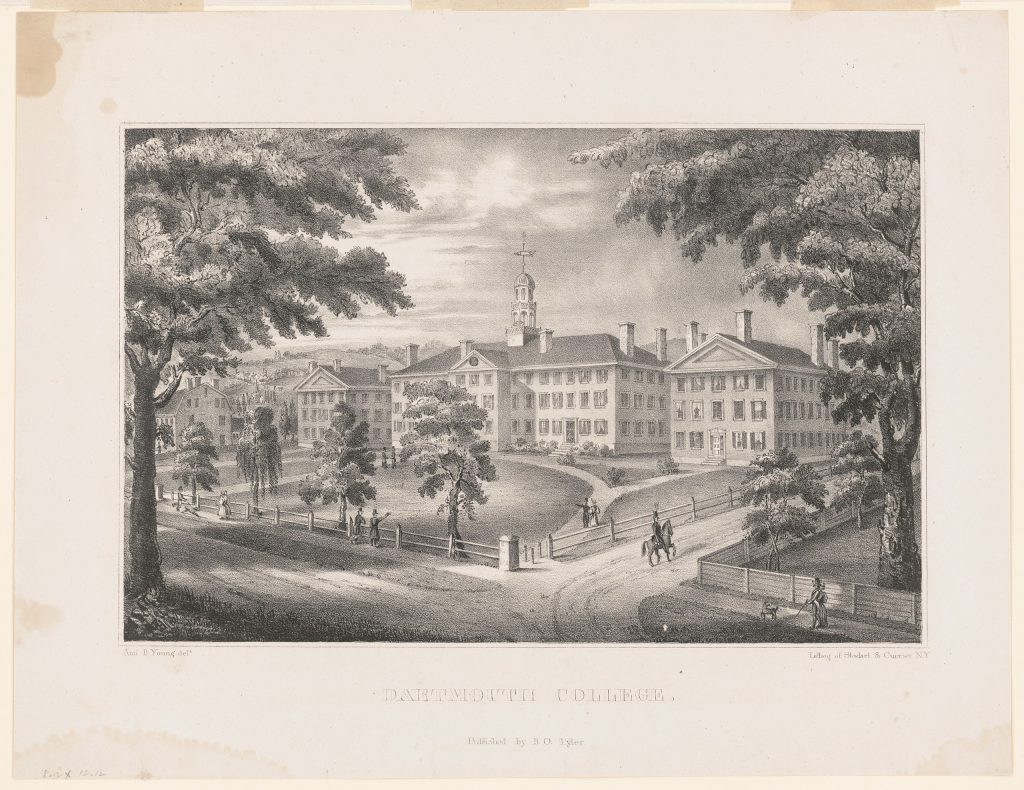

George Perkins Marsh attended a prestigious private school, Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts, before going on to study at Dartmouth. Upon graduation, he proceeded to study the law and was admitted to the bar in 1825.

He then became involved in the politics of his native state. Marsh identified with the Whig Party. Given his growing circle of friends and active participation in public affairs, in 1842, Marsh was elected to Congress from Vermont. He served there from 1843 to 1849.

The Smithsonian Institution

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

The Smithsonian Institution was founded on August 10, 1846, “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” It was named after its founding donor James Smithson.

As a member of congressional committee overseeing how Smithson’s money would be spent, Marsh determined who would serve as the curator of the Smithsonian Museum.

Spencer F. Baird

Spencer F. Baird was a protege of Marsh. He was Marsh’s choice to serve as curator of the Smithsonian Museum.

Baird built the institution’s collections, set up exchange networks around the globe and recruited a team of geologists, botanists and zoologists to go across America making discoveries and adding to the Smithsonian’s growing body of knowledge.

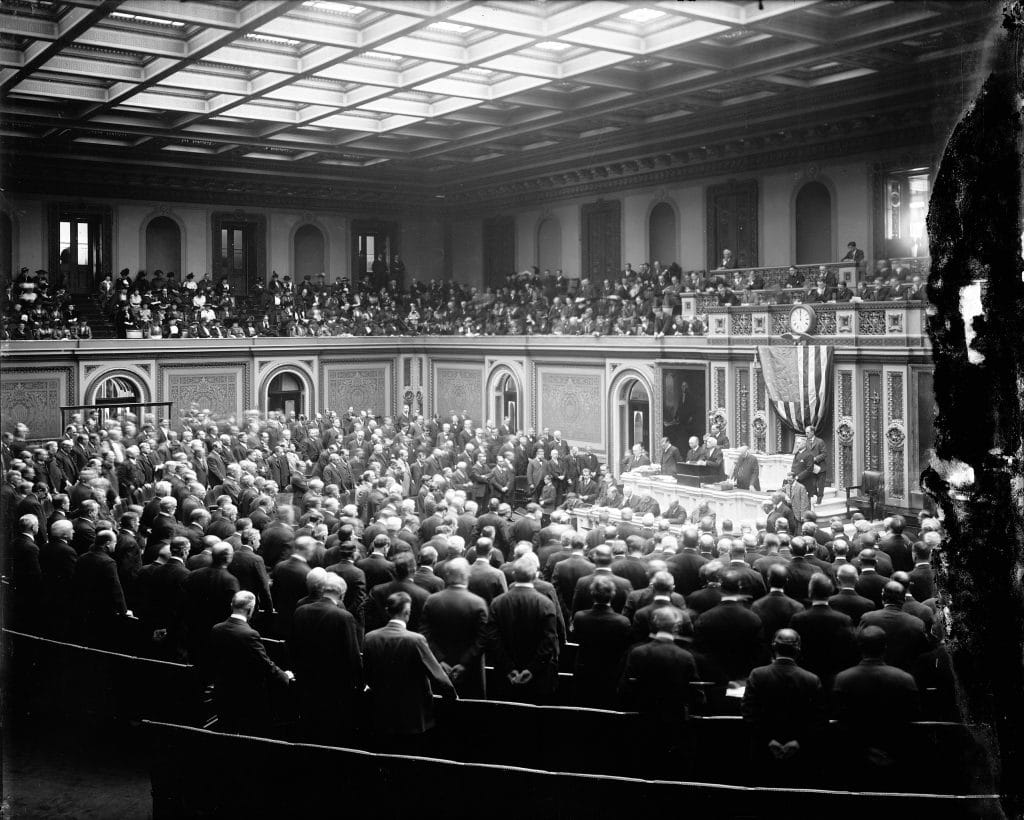

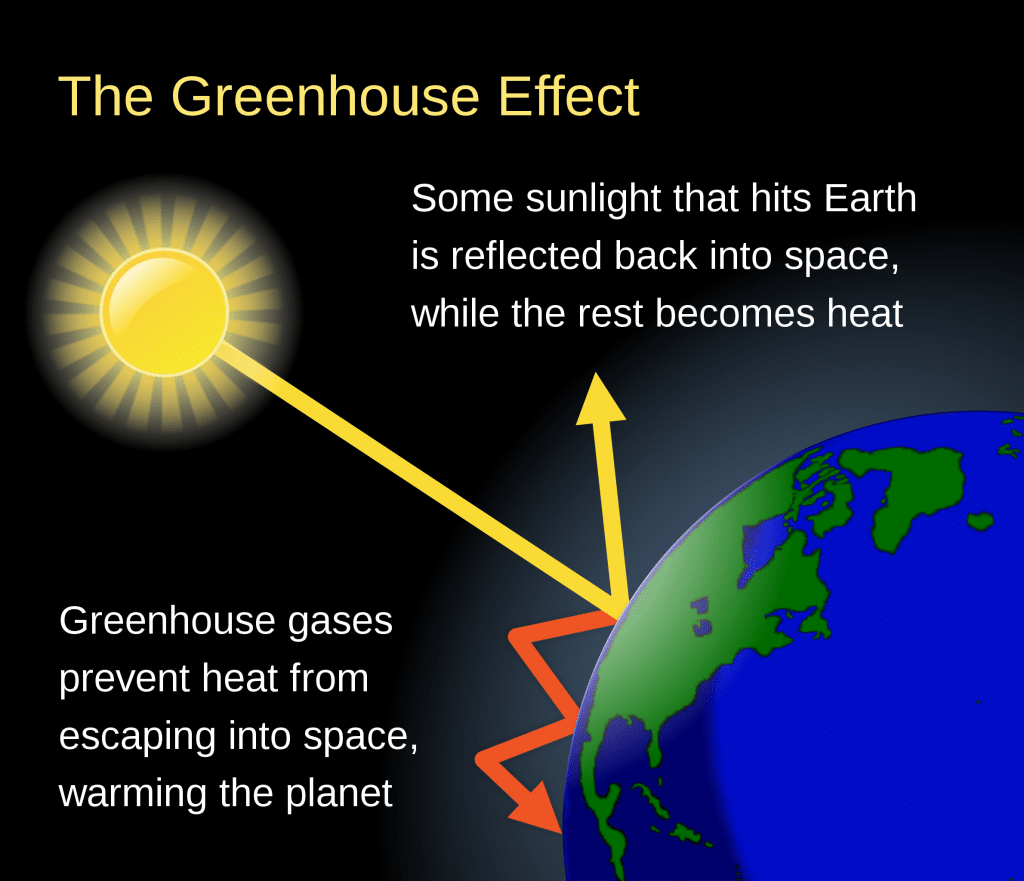

The 1847 Lecture Predicting Human-Induced Climate Change | George Perkins Marsh

Marsh’s defining moment may have come on September 30, 1847. As a congressman, he gave a lecture to the Agricultural Society of Rutland County, Vermont. In the first speech ever given to reference what today we know as climate change, the prescient Marsh had this to say:

Man cannot at his pleasure command the rain and the sunshine, the wind and frost and snow, yet it is certain that climate itself has in many instances been gradually changed and ameliorated or deteriorated by human action.

The draining of swamps and the clearing of forests perceptibly effect the evaporation from the earth, and of course the mean quantity of moisture suspended in the air.

The same causes modify the electrical condition of the atmosphere and the power of the surface to reflect, absorb and radiate the rays of the sun, and consequently influence the distribution of light and heat, and the force and direction of the winds.

Within narrow limits too, domestic fires and artificial structures create and diffuse increased warmth, to an extent that may effect vegetation. (Source: The Guardian)

In this extraordinary speech, given a decade before scientist John Tyndall first theorized about the “greenhouse effect.”

Marsh called for a more thoughtful approach to consuming our natural resources despite the consensus at the time which suggested these resources were both abundant and inexhaustible.

Ambassador Marsh

On May 29, 1849, President Zachary Taylor named George Perkins Marsh America’s Minister to Turkey. Marsh had served as a dedicated Whig in the House of Representatives and an eager supporter of Zachary Taylor.

In return, Taylor believed Marsh’s linguistic skills and widespread knowledge would reflect favorably on America’s foreign policy.

Marsh spent five years in Turkey honing his skill as a diplomat. As American Minister to Turkey, he was in a unique position to learn about how America was perceived by other nations and peoples. He also observed that the United States was not alone in its wanton disregard of nature.

“Man’s work enthralled Marsh as much as nature’s. It was thrilling to see the human past in abundant evidence. And many aspects of life–clothing, houses, farm tools and processes–seemed to him ‘just what they were in the time of the patriarchs and prophets.'”

-David Lowenthal, George Perkins Marsh: Prophet of Conservation

Return To America | George Perkins Marsh

George Perkins Marsh returned to America on August 23, 1854. Rather than focus his energies and efforts on his conservation/environmental work, however, like so many then and now, he found himself struggling with his family finances.

In Marsh’s time, government service entailed financial sacrifice. As Minister to Turkey, he was paid a fraction of his European counterparts and found himself having to pay out of his own pocket for diplomatic receptions and other important business.

Deep In Debt

By the time he returned home, Marsh was $50,000 in debt, which would be equivalent to being about $1,000,000 in debt today.

While Congress awarded him a much needed $9,000 to cover some of his overseas expenses, Marsh worked diligently to erase his debts.

He succeeded by selling many of his personal possessions. Ironically, before he would embark on his life’s most important work, he considered himself financially ruined with no prospects for the future.

Working On The Railroad

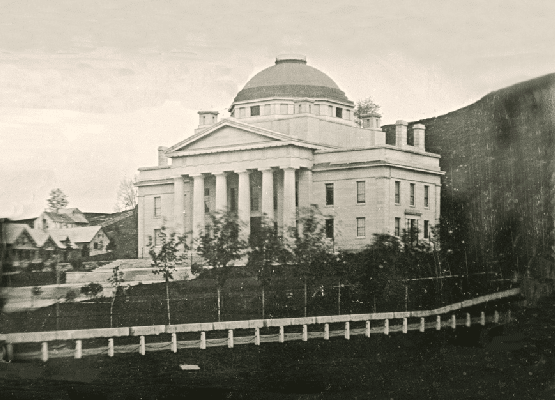

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

During his darkest days financially, as Marsh found himself unable to succeed in the world of business, he was given a lifeline. In 1857, he was appointed Vermont Railroad Commissioner.

This enabled Marsh to once again take up the cause of conservation. In addition to his railroad duties, Vermont’s Governor Ryland Fletcher made him Vermont’s Fish Commissioner as well.

Over a century before it became politically popular, Commissioner Marsh spoke out against the damming of streams and rivers. He also renewed his calls to stop the wholesale clear cutting of trees in forests which accelerated erosion and runoff.

“The clearing of woods [and] the removal of many obstacles to the flow of water [induce] more rapid drainage . . .Rain and snow find their way more quickly to the channels of the brooks [which] run with a swifter current; streams formerly clear, gentle, and equable, are now dry or nearly so in the summer, but turbid with mud and swollen to the size of a river after heavy rains or sudden thaws; torrential water courses [suffer] great changes in the configuration of their beds.”

-George Perkins Marsh, excepted from David Lowenthal’s, George Perkins Marsh: Prophet of Conservation

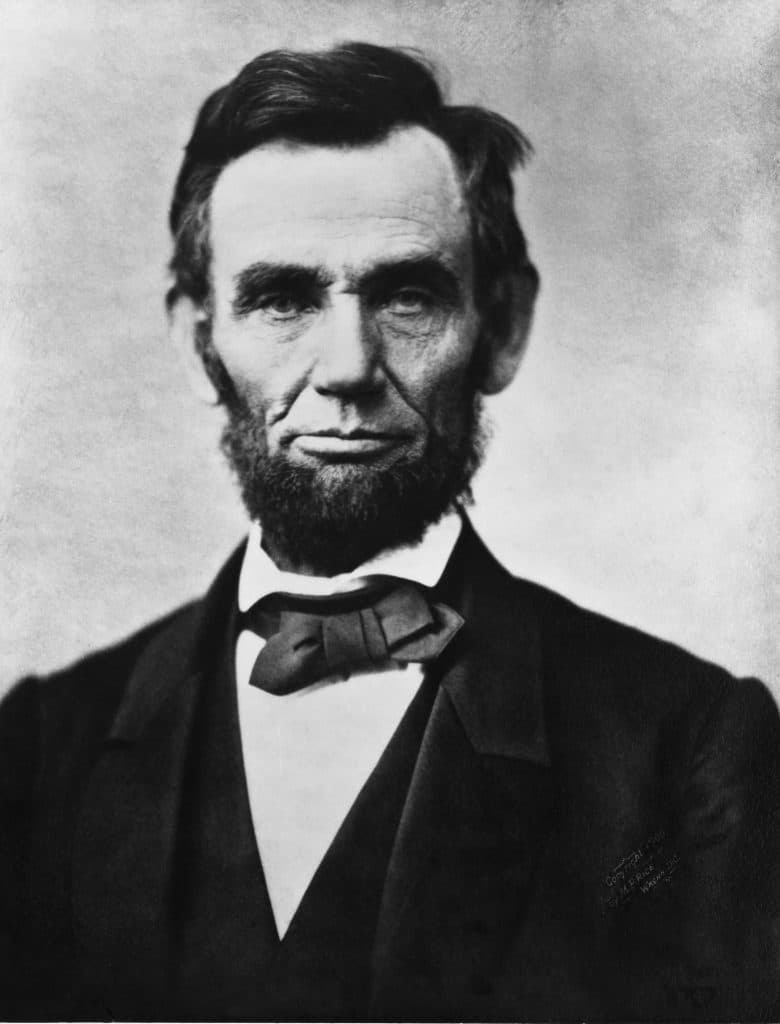

Abraham Lincoln To The Rescue

The 1850s were a difficult time for Marsh and his wife Caroline. As the nation lurched towards Civil War, the Marshes struggled with financial insolvency. Fortunately for both the Union and George Perkins Marsh, a leader came to the rescue.

With the disintegration of the Whig Party, Marsh became a Republican. In 1856, he enthusiastically supported John C. Fremont for president. Fremont lost, but four years later a fractured Democratic Party presented the Republicans with their first real opportunity to capture the White House.

Marsh Supports Lincoln

Once again, Marsh found himself supporting the Republican standard-bearer. This time, it was Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. Lincoln’s election changed the trajectory of George Perkins Marsh’s life.

Instead of spending his final years struggling to make ends meet, he would be dispatched to Europe once again where he spent the remainder of his days and produced his greatest work.

American Minister To Italy | George Perkins Marsh

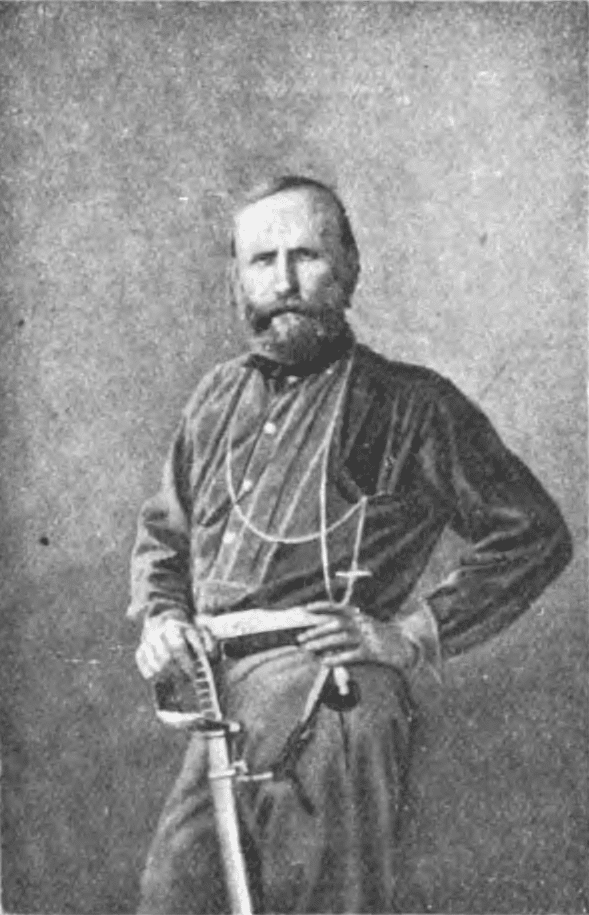

Abraham Lincoln appointed George Perkins Marsh America’s Minister to Italy. Marsh went on to serve twenty-one years at his post. This was longer than any other diplomat in our nation’s history. Marsh was present for the creation of a unified Italy in 1870.

Risorgimento, which in Italian means “rising again,” was a 19th-century movement for Italian unification culminating in the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

A process, which begin in the 1820s with the dream of a unified Italian nation-state, culminated in 1870 when Italian forces finally completed their conquest and unification with the seizure of Rome from the Papal States.

Man And Nature

As Marsh’s biographer, David Lowenthal, notes, “Man and Nature ushered in a revolution in the way people conceived their relations with the earth. It brought environmental awareness and reform not just to America, but the whole world.”

Marsh’s book begins with a discussion of the Roman Empire. He wrote about how “more than one half” of the vast and flourishing lands of the Roman Empire had lost their productivity due to mismanagement by humans, primarily deforestation.

Man and Nature traced the rise and fall of great empires, such as Rome, and made the case that their decline was connected to their physical destruction of their natural environment.

Through his research and personal observations, Marsh identified man as a “disturbing agent.” It was his hypothesis that the rise and fall of empires was inextricably linked to resource depletion.

The Conventional Wisdom Was Wrong

The conventional wisdom was that human beings were the great “improvers” of nature. This proposition was based more on faith than science. Marsh employed a scientific methodology using his decades of actual observations to challenge this proposition.

He connected the dots by documenting how empires, such as Rome, began a downward spiral when they could no longer exploit their natural resources to provide their people with an inflated standard of living. Subsequent scientific studies have validated his hypothesis.

In Man and Nature, Marsh explained how humankind was destroying its environment and what the long-term costs of such destruction would be.

His book was seized upon by conservationists in America as justification for policies to preserve and protect endangered lands. Man and Nature helped to launch the conservation movement.

“As a society increases in complexity, the investments in resource extraction, administration, organization, and defense increase. In the beginning, an increase in complexity is favorable, but there is a decreasing rate of return. This will make the society prone to collapse, because diminishing returns make complexity less attractive and increasing costs of solutions breed disaffection.

-Janssen, M. A. and M. Scheffer. 2004. Overexploitation of renewable resources by ancient societies and the role of sunk-cost effects. Ecology and Society 9(1): 6. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art6/

Taxes and other costs rise to maintain the complexity, but benefits do not rise at the same rate. Finally, the society will reach a point, given technological constraints, beyond which an increase in complexity will lead to negative returns.”

The European Example

Marsh’s Man and Nature was more than merely a catalogue of humankind’s crimes against nature. It was also a call to action.

In his capacity as Minister to Italy, Marsh was able to travel the continent and examine how Europe was attempting to reverse course following its own destructive environmental actions.

European nations had taken the lead in mandating state control of natural resources. Concepts, such as reforestation, were being introduced to replenish the natural landscape.

The Concept Of Usufruct

This led Marsh to consider the concept of usufruct–the idea that each generation had rights to current use, but not perpetual control of its natural resources.

From usufruct, Marsh was able to theorize that land use policies needed to take into consideration future generations.

This meant policies which would preserve and protect both lands and their resources. While such a concept is considered mainstream thinking since the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s, such as idea was a radical concept in Marsh’s time.

“Drawing on his extensive study of the rise and fall of ancient Mediterranean empires facilitated by his years in the region as a diplomat, the Vermont-born Marsh concluded that environmental despoliation had been central to the collapse of these once-powerful civilizations. By clearing their forests, for instance, they had unleashed a series of interlocking and escalating problems such as erosion, the silting up of streams and rivers, and the loss of soil fertility. With watersheds damaged beyond repair and agriculture faltering, the economic orders and social structures that had depended on productive landscapes were everywhere compromised.

-Char Miller, Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism

Attentive readers in the 1860s and 1870s did not miss its potent American parallels as this New World society entered an industrial age in which natural resources were being consumed with astonishing celerity. Like the Greeks and Romans, we were poised to destroy ourselves.”

Marsh’s Greatest Contribution

George Perkins Marsh spent the remainder of his life in Italy as America’s Minister. By the time of his death in 1882, he was recognized as his nation’s most skillful and experienced diplomat.

Prior to his arrival, respect for the United States was not high as a succession of mediocre political appointees had held the post before him.

The Fundamental Message

Marsh changed that. He established lasting friendships with Italian leaders including Giuseppe Garibaldi and King Victor Emmanuel.

Where diplomats before had talked of America’s greatness, Marsh listened to the concerns of his European counterparts. And he worked tirelessly to address those concerns.

Marsh’s greatest contribution was in the area of conservation and environmentalism. He was among the very first to include human impacts in our understanding of the natural world.

More than that, however, was his challenge to this notion, which dominated 19th century thinking; namely, that humankind’s efforts to shape its environment was always beneficial.

The fundamental message of Man and Nature is that nature does not heal itself from our destruction.

To Learn More About George Perkins Marsh

Today, the legacy of George Perkins Marsh can be explored at the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller Institute in Vermont or at The George Perkins Marsh Institute at Clark University. Both of these places celebrate the legacy of this extraordinary man.

At Woodstock, Vermont, you can visit the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Park which the Rockefellers donated to the National Park Service in 1992.

The park includes Marsh’s birthplace, a carriage barn which is the visitor center, and more than 500 acres of managed forestland on Mount Tom overlooking the village of Woodstock.

The Marsh Legacy Lives On

At the George Perkins Marsh Institute, Marsh’s legacy lives on. Much of their work revolves around examining one of the most fundamental questions confronting humankind: What is versus what ought to be our relationship with nature?

To learn more, I would recommend David Lowenthal’s outstanding biography titled, George Perkins Marsh: Prophet Of Conservation.

About The People Behind More Than Just Parks

We’re Jim Pattiz and Will Pattiz, collectively known as the Pattiz Brothers (and sometimes as the “Parks Brothers”).

You should probably know that we don’t just make this stuff up out of thin air. We absolutely LOVE America’s public lands and have spent our entire adult lives bringing these places to life through our amazing short films.

We’ve worked with the National Park Service, the Department of Interior, USDA, U.S. Forest Service, and more for years creating films on important places and issues. Our work has been featured in leading publications all over the world and even some people outside of our immediate family call us experts on the national parks.

And, in 2018, our father – having spent a lifetime teaching history – joined us so that he could help us to tell the incredible stories behind these amazing places.

Meet The Parks Brothers

We Hope You’ll Follow Our Journey

Our goal here at More Than Just Parks is to share the beauty of America’s national parks and public lands through stunning short films in an effort to get Americans and the world to see the true value in land conservation.

We hope you’ll follow our journey through the parks and help us to keep them the incredible places that they are. If you’re interested in joining the adventure then sign up below!

Leave a Reply