America has been blessed with a long list of famous and inspirational environmental activists. From Theodore Roosevelt to Jimmy Carter, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, John Muir, this list goes on. Environmentalism is perhaps America’s greatest national export.

It was here in America where the first conservation for conservation’s sake happened – the setting aside of Yosemite by none other than Abraham Lincoln. It was here in America that the first national park was created, Yellowstone, by Ulysses Grant.

This article is about America’s first and perhaps most influential environmental activist. A man who is responsible for the founding of some of the most influential environmental groups (outlined in this article) who some would say inspired the environmental movement worldwide.

America’s first environmental activist is More Than Just Parks first environmental hero. So, just who is this guy anyway?

It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.

― Harry S. Truman

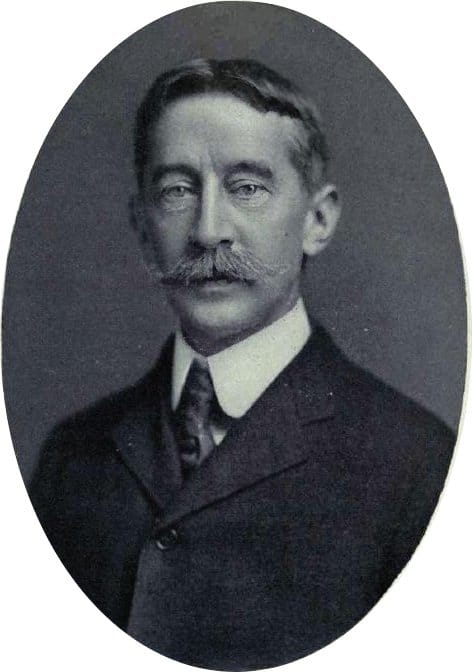

The Greatest Environmental Activist You’ve Never Heard Of: George Bird Grinnell

From a life of privilege to a life of purpose, George Bird Grinnell is likely the greatest environmental activist you’ve never heard of. Of course, if you do know who he was and what he did then keep reading as you will learn even more.

The goal is to expand your knowledge and understanding of Grinnell’s legacy and why it still matters today.

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy once said, “One person can make a difference, and everyone should try.” Grinnell not only tried, he succeeded. His fight still goes on, however, which is why his story is so very important.

George Bird Grinnell: From A Life Of Privilege To A Life Of Purpose

George Bird Grinnell was the scion of a wealthy New York venture capitalist and stock market speculator, George Blake Grinnell. His father’s influential contacts included the railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt. As a result of his financial acumen, Grinnell’s father was able to amass wealth for himself and his family.

As a consequence, George Bird Grinnell would be a child of privilege. He had access to the best tutors and was able to secure a coveted spot to Yale University. He was on the fast track for a life of comfort and ease. But while Grinnell’s friends would gravitate to the lucrative world of business he would choose a different path.

He would go to work for his father upon graduation, but then his life would take a very different turn. It would be a college trip to collect fossils during his final year at Yale which would introduce Grinnell to the natural wonders of the American West. And, this trip would forever change not only his world, but ours as well.

Expedition to the American West

Othniel C. Marsh served as Yale’s first professor of vertebrate paleontology. He recruited Grinnell in 1870 for his expedition to the American West. The purpose of this trip was to collect fossils and artifacts.

It would take Grinnell and his peers through some of the most magnificent country in America. This trip would open young George’s eyes to the natural wonders of the American West.

Upon returning home, Grinnell would continue to work for his former professor while also working for his father. He would serve in an unofficial capacity as Marsh’s assistant and help him to build an impressive collection of specimens of various wildlife creatures for the Peabody Museum of Natural History.

What began as a collaboration between two kindred spirits dedicated to the advancement of natural science would lead George Bird Grinnell away from a life as a financial speculator and towards one as a naturalist, environmentalist and champion of conservation.

From Author To Crusader | George Bird Grinnell

While he was traveling through the American West on behalf of Professor Marsh, Grinnell began writing a series of articles about his experiences.

He wrote these articles for Forest and Stream magazine. Founded by Charles Hallock in 1873, Forest and Stream was a popular publication of the day. It featured articles on hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities.

By 1880, Hallock was no longer able to fulfill his duties as publisher-in-chief. Grinnell would take over as president of the magazine. At the same time, he would also prepare for and pass his doctoral examinations in osteology and vertebrate paleontology.

Grinnell would use his academic knowledge and his outdoor experiences to transform Forest and Stream into an early champion of the fledgling conservation movement.

The national park is founded on sentiment. It is a legislative recognition of the existence in human nature of something higher than the sordid love of gain–than the mere question of dollars and cents. . .

To all that class who unblushingly place their little interests above a great public interest, who without scruple would inaugurate measures which must lead to the ruin of the National Park, Congress should oppose but one answer, and that should be written in distinct and permanent characters on every border of the Park: ‘Thus far thou shalt come and no further.’

-George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell and the Establishing of The Audubon Society

It was George Bird Grinnell who would use Forest and Stream to lead the fight against an industry which slaughtered birds for their feathers so women could proudly display them in their hats. In a series of crusading editorials, Grinnell would proclaim that “the public are awakening to see that the fashion of wearing the feathers and skins of birds is abominable.”

Grinnell would go on to establish a society for the “protection of birds and their eggs.” This society would bear the name of John James Audubon. By linking his society to Audubon, who was the premier ornithologist, naturalist and painter of the 19th century, he would raise the public’s awareness of this problem.

Grinnell called for an end to killing of any wild bird not used for food; an end to the destruction of nests and eggs of all wild birds;

and an end to the wearing of feathers for ornaments or trimming for dress.

-John Taliaferro, author of Grinnell: America’s Environmental Pioneer & His Restless Drive To Save The West

Rescuing America’s First National Park

Yellowstone National Park was established by an act of Congress which was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872. Ten years later, however, America’s first national park was in danger of becoming its last.

A contract, which was negotiated between the Department of the Interior and the Yellowstone Park Improvement Company, gave the private company the right to “rent” the park out to private parties.

These groups do whatever they wished. This included the wholesale slaughter of the park’s animals. Imagine a private preserve where guests could treat one of our nation’s greatest treasures as their own personal property and do whatever they wished irrespective of the cost.

For George Bird Grinnell, efforts to defile Yellowstone meant the ultimate destruction of some of America’s most precious lands. Proving, once again, that the pen is mightier than the sword, he sounded the alarm in a series of blistering editorials in Forest and Stream.

His editorials would be carried in America’s leading newspapers. By defending Yellowstone against commercial interests, Grinnell would establish himself as the leading voice of the nascent conservation movement.

And, he did this long before Theodore Roosevelt would be able to use the powers of his great office to protect these sacred places.

An Inflection Point During the Age of Industry

Grinnell understood that America was at an inflection point where the Age of Industry, which had catapulted the U.S. economy to the global forefront, was now in a position to pursue its profits in reckless and dangerous ways. These would include the exploitation of the American West.

Grinnell printed weekly editorials promoting legislation to protect Yellowstone by ensuring that it would be managed solely by the federal government.

He also recruited prominent politicians, such as Commissioner of the U.S. Civil Service Theodore Roosevelt, Speaker of the House of Representatives Thomas Reed and others, to lead the fight in Washington.

By focusing on the imminent threat to Yellowstone from unbridled corporate interests and the poaching they encouraged, Grinnell was instrumental in helping to secure passage of the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act in 1894.

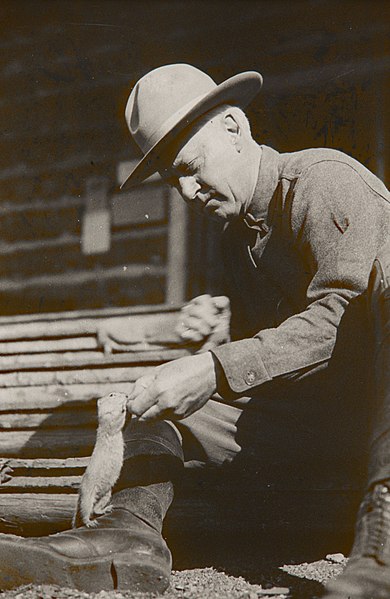

This act protected the wildlife in Yellowstone National Park. It punished crimes committed in the park. It also helped bring about the establishment of park rangers who would ensure the preservation and protection of Yellowstone and other national parks and forests.

Grinnell called for the creation of troops to be stationed in these places to protect them from those who would do harm. Most importantly, however, these early actions would serve as a deterrent to powerful business interests.

Big business became fearful that the consequences of their profiteering could prove too costly in the court of public opinion.

Founding The Boone & Crockett Clubs | America’s First Environmental Activist

Another way in which George Bird Grinnell would protect America’s wildlife would be through the establishment of North America’s oldest wildlife conservation organization. Grinnell, along with Theodore Roosevelt, founded the Boone and Crockett Clubs.

The mission of these clubs was to “promote the conservation and management of wildlife, especially big game, and its habitat, to preserve and encourage hunting and to maintain the highest ethical standards of fair chase and sportsmanship in North America.”

With the enthusiastic support of Boone and Crockett Clubs nationwide, Congress, in 1900, passed America’s first wildlife conservation measure, the Lacey Act. This bill banned commercial hunting and interstate transportation of game. It also put an end to the importation of exotic species.

The earth has music for those who listen.

—William Shakespeare

On March 14, 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt would establish the Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge as the first unit of what would become the National Wildlife Refuge System. For Grinnell and other wildlife preservationists, Roosevelt’s actions were long overdue.

Roosevelt would, as president, establish wildlife sanctuaries throughout the United States for the protection of endangered species. By the time his tenure in office ended, he would establish over fifty of these sanctuaries.

Here is this Yellowstone Park. The large game of the West may be preserved from extermination.

-George Bird Grinnell

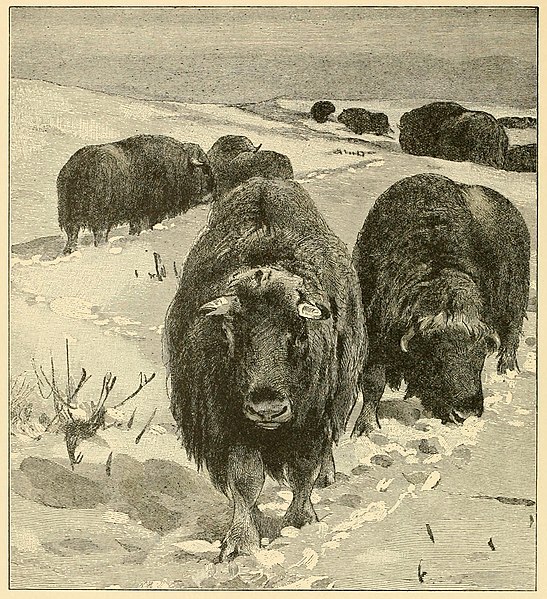

Loose Moose Morals

George Bird Grinnell was a hunter and a sportsman. As he grew older, however, he understood the necessity of preserving and protecting all species. He became a champion of laws intended to protect wildlife from hunters and sportsmen.

Writing one editorial under the heading of “Loose Moose Morals,” Grinnell would exclaim, “It is high time that offenders against game laws should stop boasting of their exploits.”

Grinnell was increasingly concerned by the proliferation of poachers and commercial hunting interests who were decimating the pristine wilderness of the American West. He would help to establish ground rules ensuring the preservation of a variety of species.

Environmental Inspiration for the Ages: Theodore Roosevelt & George Bird Grinnell

Grinnell’s efforts to protect wildlife from decimation at the hands of commercial hunting would serve as a forerunner of the later efforts of organizations, such as Green Peace, to protect endangered species around the planet.

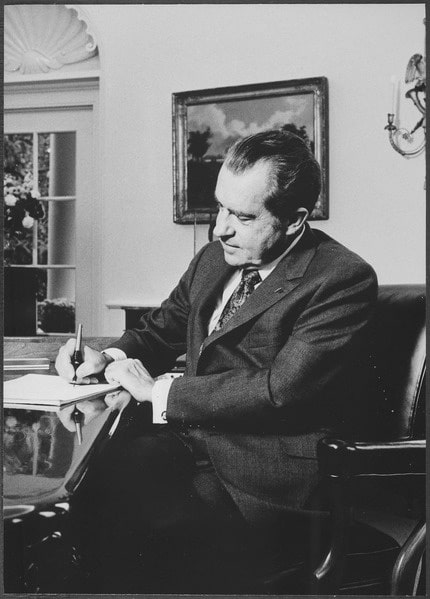

Theodore Roosevelt’s efforts to establish wildlife sanctuaries would serve as the forerunner for the 1973 Endangered Species Act.

Together, these two men would demonstrate the power of public action to serve as a counterweight to private industry when it came to protecting the larger interests of all Americans including generations yet to come.

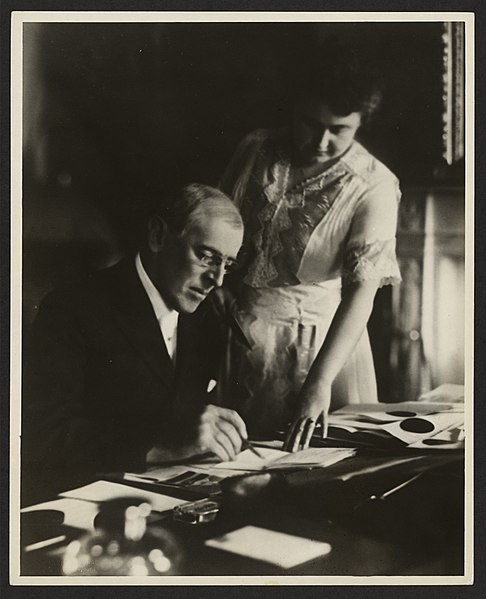

Signs The 1973 Endangered Species Act. (Courtesy Of Wikimedia)

We have become great because of the lavish use of our resources.

But the time has come to inquire seriously what will happen when our forests are gone, when the coal, the iron, the oil, and the gas are exhausted, when the soils have still further impoverished and washed into the streams, polluting the rivers, denuding the fields and obstructing navigation.

-Theodore Roosevelt

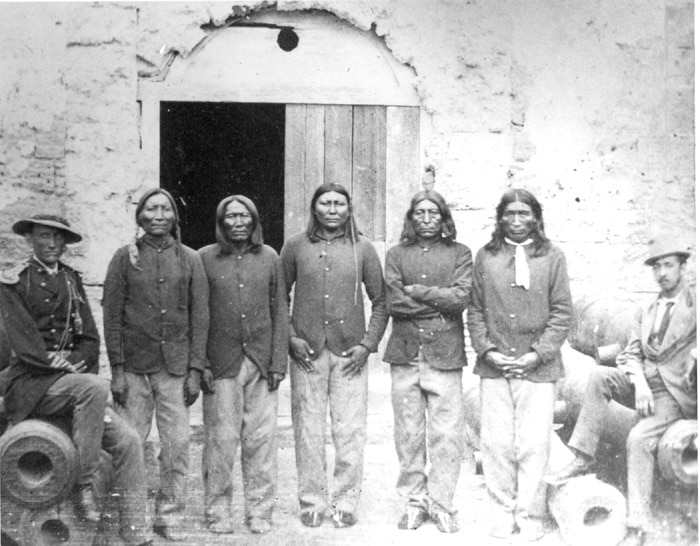

Speaking Out On Behalf Of Native Americans

George Bird Grinnell not only loved the land, he grew close to those who were its original stewards–the Native Americans. Grinnell would spend his entire life learning about their past and chronicling their achievements for an America which would see them as uncivilized.

The popular image of Native Americans as barbarians and savages would serve as a rationale for seizing their lands and undermining their heritage.

Grinnell would push back against these efforts by using his gifts as an author to challenge the prejudices of his time. He would write, “We are too apt to forget that these people are humans like ourselves. That they are fathers and mothers, husbands and wives, brothers and sisters; men and women with emotions and passions like our own.”

The most shameful chapter of American history is that in which is recorded the account of our dealings with the Indians.

The story of our government’s intercourse with this race is an unbroken narrative of injustice, fraud, and robbery.

Our people have disregarded honesty and truth whenever they have come in contact with the Indian, and he has had no rights because he has never had the power to enforce any.

-George Bird Grinnell

When Grinnell would travel west to the great outdoors, he would make time to interview Native Americans. His goal was to learn about their customs, cultures, traditions and, most importantly, their storied past.

He believed it was important for their history to be told. And, he wanted to tell it.

Grinnell would produce an impressive body of scholarship which did just that. In this regard, as in so many others, he was a man generations ahead of his time.

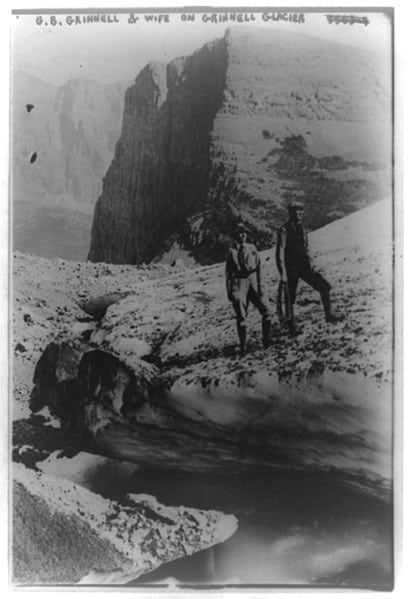

The Prize He Most Desired | Grinnell & Glacier National Park

As Grinnell biographer John Taliaferro writes, “Glacier National Park was the prize which George Bird Grinnell most desired.” He first visited this magical place as a young man in 1885.

Six years later, in Forest and Stream, he would call it the “crown of the continent.” As one of the first Americans to visit and record his impressions of Glacier, Grinnell would have the honor of having a glacier, a lake and a mountain named after him.

From the time he first dreamt of it becoming a national park in 1891, he would work tirelessly to gather support for this idea. Grinnell’s editorials in Forest and Stream, as well as his efforts to lobby political leaders such as Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, would finally bear fruit.

In 1910, almost twenty years after he first decided it should be designated a national park, his efforts would finally be rewarded.

Congress would pass and President William Howard Taft would sign the bill designating it as Glacier National Park.

Fast forward to 2019 and over three million visitors, in that year alone, would have the opportunity to see for themselves what Grinnell first saw in 1885 when he fell in love with the place he would call the “crown of the continent.”

Creating A National Park System | Greatest Environmental Activist

Stephen Mather, who would serve as the first director of the National Park Service, would also prove to be the guiding force behind the legislation creating a unified system of national parks.

Long before Mather came onto the scene, however, it was George Bird Grinnell who would call for troops to be stationed inside of these parks to protect their natural treasures.

And, it would be Grinnell who would lend his influential voice and his unstinting support to this idea of creating a unified system of parks which would be controlled, preserved and protected by the federal government.

That dream would become a reality in 1916 as Congress passed and President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation creating the National Park Service.

It was Grinnell’s heartfelt belief that what mattered most was not who received the credit, but that actions would be taken which would serve the greatest good. This would summarize his lifelong crusade to preserve and protect America’s greatest national treasures.

Quoting Grinnell, “I think that one reason why preservation matters have gone so slowly in this country is because a lot of us have been continually squabbling over who should get the credit of having done something or started something. My view for a good many years has been to try and get results.” And, get results he did.

You and I and the rest of our generation are now getting within range of the rifle pits.

We, all of us, have to face the same fate a few years earlier or a few years later, and I think what really matters is that, according to our lights, we shall have borne ourselves well and rendered what service we were able as long as we could do so.

-Excerpt of a letter from Theodore Roosevelt to George Bird Grinnell, courtesy of John Taliaferro, Grinnell: America’s Environmental Pioneer & His Restless Drive To Save The American West

A Call To Serve | Greatest Environmental Activist

Before Rachel Carson and Silent Spring, before Theodore Roosevelt and the Antiquities Act, there was George Bird Grinnell. He would use his wealth and his privileged position in society to acquire a magazine, Forest and Stream.

His magazine would become his megaphone. Grinnell would use it to champion the cause of conservation throughout his lifetime.

He would be instrumental in influencing political leaders and shaping public policy. Grinnell would doggedly pursue an ambitious agenda to preserve and protect America’s national treasures; its waterways, its glaciers, its mountains, its parks, its forests, and much, much more.

Grinnell would also champion the protection of America’s wildlife. He established the Audubon Society to eliminate the senseless slaughter of migratory species.

Grinnell founded the Boone and Crockett Clubs to set limits on the hunting of game, large and small. He would urge leaders of government and industry to pass laws which would encourage the long-term survival of these endangered species.

Grinnell & Public Lands | Greatest Environmental Activists

Through his editorials, George Bird Grinnell would become laser-focused on ensuring that our nation’s public lands would be preserved and protected for generations yet to come.

In this regard, he became the midwife to a nascent environmental movement and the conscience of conservationism from its earliest days.

That conservation movement would produce other leaders who would champion the public good. Men such as Stephen Mather and his assistant Horace Albright.

Mather, inspired by Grinnell and the example which he set, would also leave behind a life of privilege and oversee the creation and administration of a unified system of national parks for the people to enjoy.

The Legacy of George Bird Grinnell | Greatest Environmental Activist

What Grinnell, Mather and Roosevelt had in common was an understanding that privilege meant responsibility and a call to service. First and foremost, it meant the responsibility to build a better world for everyone.

Unlike those who would pursue wealth for their personal aggrandizement and whose guiding principle was one of self-interest, these men would move from a life of privilege to a life of purpose.

They would give back to the larger society and, in doing so, create a vital legacy for all of us to enjoy. Their example would remind us, however, that we must do our part to address the unprecedented challenges and dangers to these special places in our own time if we are to ensure their survival.

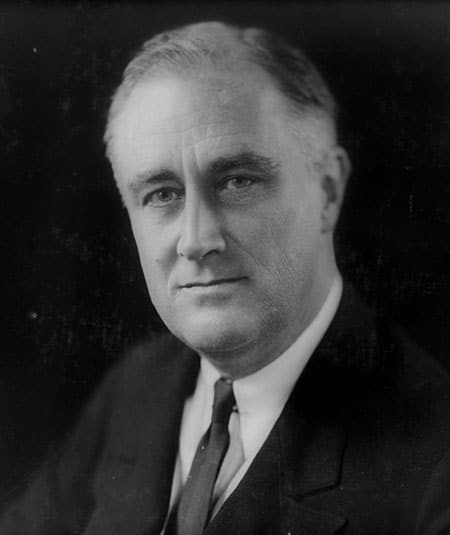

The legacy of George Bird Grinnell and Theodore Roosevelt would leave its mark on the generation which followed. That generation would produce a different Roosevelt. He would come from a different political party, but understand that preserving and protecting our nation’s greatest natural wonders is not a partisan responsibility. It is an American responsibility.

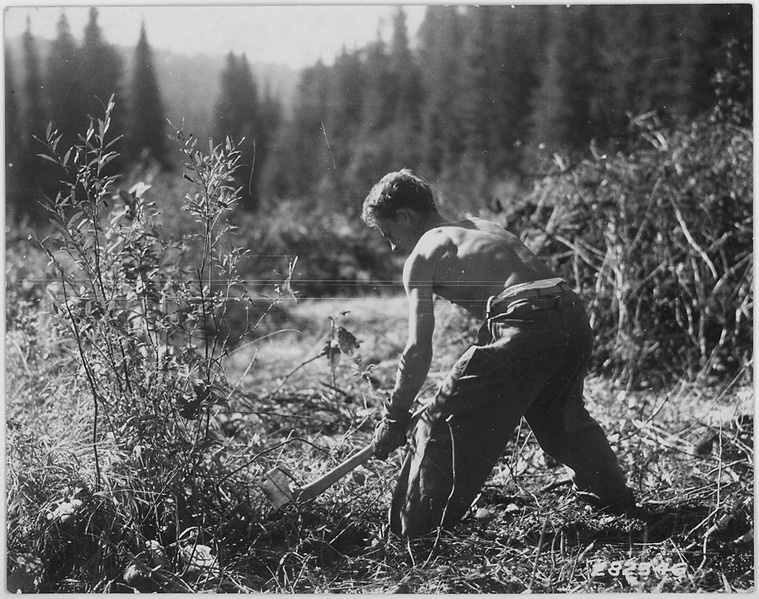

Franklin Roosevelt would stand on the shoulders of these conservation giants and continue their important legacy. He would create a Civilian Conservation Corps to conserve and protect the country’s natural resources while providing jobs for unemployed young men during the height of The Great Depression. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps would, to borrow a more contemporary phrase, “build back better.”

Soil Conservation Act | America’s First Environmental Activist

Congress would pass and President Roosevelt would sign the Soil Conservation Act. Twenty thousand Civilian Conservation Corps workers would be deployed to work in the new Soil Conservation Service.

In the wake of the terrible Dust Bowl and drought of the 1930s, which would decimate midwestern agriculture, the Roosevelt Administration would combat a changing climate by planting an estimated 200 million trees from Texas to the Canadian Border.

Under Roosevelt, government would make valuable contributions to forest management, flood control, conservation projects, and the development of state and national parks, forests, and historic sites.

The Lesson of America’s First Environmental Activist

The lesson of America’s first environmental activist is that it’s up to each of us, irrespective of our economic station or political philosophy, to do our part. Once upon a time, preserving and protecting our national treasures was a responsibility championed by leaders of both political parties.

This should not be a partisan issue. We should ensure that these natural wonders, which rightfully belong to all of us, will continue to be preserved and protected for generations yet to come. Greed and self-interest are as old as human history, but so is the desire to serve others and leave the world a better place than we found it.

George Bird Grinnell answered the call to serve. If the magnificent public lands which he spent a lifetime protecting are to survive and flourish in the future then it’s up to each of us to answer a similar call.

For, as Theodore Roosevelt once said to his fellow conservationist, “I think what really matters is that, according to our lights, we shall have borne ourselves well and rendered what service we were able as long as we could do so.“

Defenders of the short-sighted men who in their greed and selfishness will, if permitted, rob our country of half its charm by their reckless extermination of all useful and beautiful wild things sometimes seek to champion them by saying the ‘the game belongs to the people.’

So it does; and not merely to the people now alive, but to the unborn people.

“The ‘greatest good for the greatest number’ applies to the number within the womb of time, compared to which those now alive form but an insignificant fraction.

Our duty to the whole, including the unborn generations, bids us restrain an unprincipled present-day minority from wasting the heritage of these unborn generations.

The movement for the conservation of wild life and the larger movement for the conservation of all our natural resources are essentially democratic in spirit, purpose, and method.

-Theodore Roosevelt

Leave a Reply